The Way of the

Forge: The Art & Craft of Bladesmithing

by Matsu Katsumoto,

translated by Andrew L (limsk@jhancock.com.my)

"The Sword is the Soul of A Samurai"

Reality Check

There is a certain 'mystique' and plenty of accumulated bladelore surrounding traditional Japanese blades. Stories of magical strength and cutting ability are mentioned in the same breath as the legendary exploits of the Samurai and Ninja. Tales are told of how they can cut lesser swords in two, or sever the stem of a lotus flower as it floated past in a stream.

Some of the more outlandish stories are probably untrue. From historical accounts, swords often broke in battle, despite their carefully crafted blades. Japanese blades were designed to defeat light armour and in this respect, they perform superbly. Fighting edge-to-edge was a different matter entirely and no steel (including modern alloys), no matter how well made, will withstand such abuse. The antique blades that have survived to present times probably did so because they were never used in a real battle.

Still, this is Rokugan, where magic works, and good swords can indeed last forever!

Foreward by Matsu Katsumoto

The art of crafting fine blades is an ancient and honoured tradition and there are many blademaking families among the artisans of Rokugan. My own family has recorded 12 generations of bladesmiths, the first being my revered ancestor, Matsu Noburo. I, Matsu Katsumoto, learnt the craft at the feet of my honourable father, Matsu Iesada. He in turn, learnt it from his father before him, thus handing down the skill and knowledge accumulated over more than six centuries of unbroken lineage.

While the the bladesmith's craft is deep indeed, it remains very much a verbal tradition and precious little has been set down on paper. For some time now, our honoured family Daimyo Matsu Yukiko has expressed concern that such important lore was not recorded for future generations. Thus, at Yukiko-sama's request, I have compiled all the blademaking knowledge as known to my family and our allies, to be preserved in the archives of the Lion Clan. Now, having commited the last brush stroke, I can only hope that our family's treasured lore will be of benefit to future students of the blade.

Matsu Katsumoto

67th day of the reign of the 31st Hantei

History & Evolution: The Craft of the Bladesmith

While it is not recorded which ancient bladesmith made the first great blade, swords and bladed weapons have been in use since the beginnings of our history. The earliest blades still preserved in the collections of the daimyos of Rokugan are of beaten iron. These blades were typically broad, straight, and heavy, quite unlike the blades in use in current times. While flexible to the point of unbreakability, the soft iron blades bent easily and dulled quickly with use. Some of the oldest scrolls in the possession of the Lion historians have mentioned that Bushi often had to stomp their swords straight after a battle.

The shortcomings of crude iron were overcome with the discovery of steel. The honourable smith who first accomplished this monumental deed is a subject of great debate among the Great Clans. This can be expected, as history is often coloured by the efforts of historians keen to show their Clan in the best possible light. As I am not a historian, I leave this matter for more cultured minds to argue. Scrolls in the Lion Clan's posession attributes the honour to Ikoma Yutaka, who was later made personal bladesmith of the 1st Hantei.

How Yutaka-sama came upon this knowledge is unclear. An old story relates how Yutaka-sama, in his quest for the perfect blade, travelled across the mountains. When he returned, he bore a sword forged of a silvery metal that when bent sprang straight again and could cut good iron as if it were wood. While other more outlandish folk tales exist concerning the discovery of steel which involve Tengu or Hengeyokai, many bladesmiths including myself are inclined to doubt their authenticity.

Regardless of its method of discovery, steel has thus far proven to be the most suitable blade material and has been universally used for weapons by all the Great Clans of Rokugan. Forged from raw iron infused with the essence from a coal forge, steel is far more useful than simple iron. Great strength, flexibility and cutting ability are all possible when the correct skill and methods are applied. An accomplished bladesmith coaxes such attributes from the steel, similiar to the way a fine sensei coaxes ability from his students.

The process of refining raw iron ore into steel is involves much labour. The raw iron ore is first smelted in a tatara (charcoal furnace) to drive off impurities and infuse the iron with the essence of the coal fire. The end result is tama-hagane, a fused chunk of metal with a blue sheen and flecks of gold. Composed of iron and steel of varying hardness, from very hard to very soft, the tama-hagane is carefully broken up into smaller pieces using a large hammer. The pieces would then be sorted and graded by the bladesmith's experienced eye, selecting the best pieces for further work.

Once he had sufficient material, the bladesmith would heat the pieces in a coal forge, before fusing the pieces together with a hammer to form a crude bar. This bar is then folded and welded several times to refine the metal, losing about half the material in the process. When several such bars are completed, they would be stacked together, and hammer-welded to form a rough blade. This layering of steel and iron during the forging results in a unique pattern or texture which is clearly visible once the completed blade is polished. More importantly, this 'thousand-fold' technique produced steel with great flexibility and toughness and provided better raw material for blades.

To promote flexibility the bladesmith would often 'fold' a soft bar of iron inside an outer skin of steel. This particular process calls for great skill in manipulating the hot metal with a hammer and is typically beyond the ability of apprentices. Often, despite the best efforts of the smith, the iron core refuses to remain in the center of the blade and the work has to be discarded. In one recorded story, Ikoma Yatsuda was said to have reforged a blade a hundred times. Before the hundredth attempt, Yatsuda-sama swore he would give his life to see the blade forged. The blade was sound, and Yatsuda-sama committed seppuku. His son and apprentice, Ikoma Okuda completed his work.

It should be noted that the detailed forging methods of the master bladesmiths are among the most treasured of knowledge in Rokugan. Each clan has its own method and secrets which they divulge to no one, not even their allies. While it is common for a bladesmith to discuss blademaking techniques with other bladesmiths, it is highly unlikely that a bladesmith from a different family would be allowed to watch a forging. In my family's six centuries of crafting blades, no bladesmith of my line have ever been allowed into the forge area of another Clan. While the basic methods used are well-known to all bladesmiths, each bladesmith typically forges a blade with a technique so unique that their work may be identified from studying the patterns in the steel. Naturally, it would take a great deal of knowledge and experience to accomplish this.

Traditional

painting of a bladesmith at work

[Click thumbnail for larger image]

Besides steelmaking, the other great discovery of Rokugani bladesmiths is the secret of water-quenching. This discovery was made by an apprentice, Agasha Hogai during the reign of the 11th Hantei. While an apprentice, Hogai was noted by his bladesmith sensei (and uncle) Agasha Gobei as 'having a keen mind despite being fumbling and inept'. While pondering the nature of the universe (as described in many plays), Hogai dropped a red-hot partly completed blade into a pail of water. Agasha Gobei only discovered what his apprentice had done when despite his best efforts to shape it, the blade refused to move under his hammer. Quickly realizing the value of such a discovery, he spared Hogai a sound beating when the apprentice confessed.

The intricate details of what happens to steel during quenching is not entirely understood, even to bladesmiths like myself. My research into this phenomenon, including discussions with the elemental masters of the Phoenix Clan have so far failed to provide any insight. I remain convinced that the answer will someday be revealed. What is certain, however, is that the rapid cooling in water causes certain changes in the structure of the steel, resulting in increased hardness. There are as many ways of quenching as there are bladesmiths. Some favour the waters of a certain district or held at a particular temperature. Often, special ingredients are added to the water; my own school of swordmaking favours boiling salt water for quenching. At least one famous bladesmith has been rumoured to have quenched his blades in fine sake.

Regardless of how it was accomplished, this quench-hardening first appeared to be beneficial to the blade, for it cut well and the edge did not wear away easily. It was soon discovered that increased hardness was not the perfect answer. Blades crafted entirely of very hard steel proved to be brittle and easily broken by a sharp blow. Ideally, the perfect blade would have a very hard yakiba (edge) graduating to a very flexible mune (spine). Such a blade would cut through armour with ease, and yet spring with a blow, preventing breakage. Experiments in water-quenching by later generations of bladesmiths provided the answer.

It was discovered that the speed at which the red-hot blade was cooled altered its properties significantly. When cooled quickly, the steel became hard and became extremely difficult to shape or forge. When cooled slower, as when wrapped in some heat-resisting material, the steel remained soft and flexible. While it is not known who first used the technique, by the time of the 13th Hantei, bladesmiths were coating their blades with clay before quenching. By varying the thickness of the clay coating, bladesmiths were able to control the cooling rate of the hot steel on different sections of the blade.

The clay was thinnest on the edge, graduating to thickest on the back of the blade. This allowed the water to cool the steel at the edge rapidly, producing maximum hardness. The back or spine, insulated with a thick layer of clay cooled slower, resulting in a soft, flexible structure. The different grain structures on the blade often results in a wavy line that runs all the way along the edge of the blade. This hamon (tempered line) is a unique characteristic of blades crafted using this clay-tempering method. The pattern of the hamon is often enough for the experienced eye to determine which bladesmith, or at least which Clan or school made the blade.

One other item worthy of note is that bladesmiths do not actually forge their blades curved. The curve present in all Rokugani katana and wakizashi are the result of clay-tempering and quenching. Blades are forged mostly straight and as they are quenched, a strange phenomenon occurs. When thrust edge-down into the quenching water, a blade first curves downward like a sickle. As the steaming blade is held under the water, it slowly begins to curve upwards until it reaches the shape the bladesmith desires at which point it is removed from the water. Quenching is arguably the most difficult of the bladesmith's tasks - weak attention at this point results in a ruined blade which has to be discarded.

If all is well, the blade is then ground to its final shape on a large grindstone with a stream of cool water playing over it to prevent heating and possible degradation of the hardened edge. The sharpened blade is then laboriously polished using a series of limestones, to bring out the details of the hamon and to make the blade more rust-resistant. This work can be as time consuming as the actual forging itself, and is considered by many a craft by itself. A bladesmith can easily use 12 - 15 different stones and spend 100 - 200 hours polishing one katana blade. Once polished, all that remains is the crafting of the scabbard and fittings.

With these techniques, bladesmiths forged the legendary blades of Rokugan which could cut superbly and yet were light and flexible enough to resist breaking. The centuries of Inter-Clan warfare no doubt provided practical experience for the evolution and development of swords and other weapons. The earlier heavy, straight broad blades evolved into narrower blades with a distinctive slow, graceful curve. It was discovered early that curved blades cut better than straight blades on a slice stroke, which is the predominant stroke in classical kenjustsu. Of the major offensive techniques, only one is a thrust attack - to the throat. There are many practical reasons for this.

Firstly, reaching the vitals of a well-armoured, fairly skilled opponent with a thrust is all but impossible. In addition, a deep thrust often delays recovery of the weapon, a delay which could prove fatal in the chaotic melee of battle. By comparison, severing an arm, leg, or the head ends the encounter decisively and the follow through would put weapon on guard again for instant use. The curved blade assists the elliptical slice motion, causing the edge to drag through a cut, thus improving its cutting power. By keeping the curve slight, the blade preserved its reach and thrusting potential, achieving true functional perfection in bladed weapon design.

Many of the scrolls in the possession of the Unicorn mention the superiority of their blades when matched against gaijin foes bearing foreign-made weapons. In their long journey in the lands beyond the mountains, our Unicorn brethren were involved in many wars and skirmishes with dissimilar foes. One story relates how Otaku Yukio, a Unicorn battle-maiden defeated a barbarian chieftain in combat by cutting in two, first his spear, then his shield, and finally his sword, all as if they were bamboo. Her blade, forged by the master bladesmith Shinjo Hirobei did not even nick from the effort. Left unarmed and speechless, the chieftain and his men surrendered to Yukio-sama.

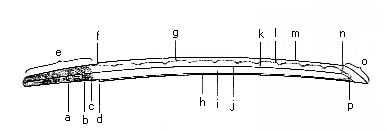

Blade Terminology

|

a. mei - signature b. mekugi-ana - peg hole c. yasuri - file marks d. mune machi - back shoulder e. nakago - tang f. ha machi - front shoulder g. hamon - temper line h. mune - spine |

i. shinogi ji - upper blade surface j. shinogi - ridge k. jigane - lower blade surface l. yakiba - hardened edge m. ha - blade edge n. yokote - transverse ridge o. kissaki - blade point p. ko shinogi - blade surface at point |

Sword Testing

All swords made by bladesmiths of any appreciable skill are tested for their strength and cutting ability. It is my belief, that one cannot be a bladesmith without understanding how blades are used. These tests, often performed by the bladesmith himself, or expert sword testers, are called tameshi-gari (target-cutting). Common methods included cutting a variety of materials, notably bamboo, packed rice-stalks, or less frequently, dead corpses. In some cases, blades were tested on condemned prisoners or innocent peasants as well, an act called tsuji-gari, although we of the Lion Clan frown upon such practices.

Typically, these sword tests are conducted with some ceremony, especially for blades destined to be worn by Clan or family Daimyos. A master swordsman would make the cut from his extensive reportaire, and the sword later examined by expert witnesses to confirm the quality of the blade. A good blade should cut deep, and not nick, bend or break. Rokugani blades are justly famed for their outstanding cutting ability. The records of my family detail one such test-cutting where a blade made by the renowned master bladesmith Matsu Kagero sliced through a pile of seven corpses, a sack of sand, and the wooden bench on which they were laid with one cut.

It is common practice for bladesmiths to sign their work by chiselling their Clan and name onto the blade. This is often done on the nakago (tang), the handle part of the blade. Often, the signature of the sword tester is also inscribed on the tang, opposite the smith's. On especially fine blades, the marks may be inlaid with precious metal. However, some of the most accomplished bladesmiths scorned this practice as they felt that anyone worthy of their blades should recognize the maker by the quality of the sword or knife alone.

The Bladesmith

It has been mentioned that the bladesmith's craft is an honoured tradition in Rokugan. This is hardly surprising, given the reverence of the sword in Rokugani society. The great bladesmiths of Rokugan are known throughout the Emerald Empire, and their perfect, handmade blades are prized by emperors and samurai alike. However, like many family traditions, one usually has to be born into a family practicing such crafts to become a bladesmith. This has resulted in a number of famous blademaking families, of which I humbly include the Matsu of the Lion Clan. Some of the other families famous for their blades are the Agasha of the Dragon Clan, the Kaiu of the Crab Clan, and the Kakita of the Crane Clan.

Each bladesmith has a select team of apprentices, frequently from the bladesmith's own family who assist in the forging and crafting of his blades. These apprentices perform most of the less demanding tasks in the smithy, including the gathering of wood to make charcoal, and the breaking up of rough iron ore. In time, with the sweat of much experience, these apprentices learn the true skills of a bladesmith. They learn how to maintain a constant coal fire, judge the heat of the steel by its colour, and manipulate the hot steel efficiently with a heavy hammer. This process may take up to 10 years before an apprentice is practised enough to begin crafting his own blades. Upon the death of the bladesmith, his most senior apprentice takes over his forge, thus continuing the traditions handed down by his sensei.

Many bladesmiths, including myself, believe that there are mystical powers at work in every forging. The act of drawing from the essence of the five elements imbue the smith with a spiritual connection to the elements which I have not experienced anywhere else. The metal of the Earth, the Fire of the forge, the Wind from the bellows, the Water of the quenching, and the Spirit (Void) of the bladesmith all combine to produce a well-crafted blade. Even the least devout of my brethren are convinced that the maker passes a little of himself into each of his blades, imbuing them with life.

Two of the greatest swordsmiths in Rokugani history are the noble Mirumoto Yoshimune and the infamous Hida Morimasa. Yoshimune is generally considered the greatest of all Rokugani swordsmiths, and was known for his charisma and nobility of character. His incomparable blades are said to reflect this nobility and are highly prized as heirlooms of the samurai families. Morimasa, a brilliant but somewhat unstable smith made superb blades famed for their awesome cutting ability but had an uncanny tendency to bring their owners into violent conflict with others. A Morimasa blade, it was whispered, could never rest peacefully in its saya (scabbard). One old story related to me by a travelling monk tells how leaves floating on a stream avoided the blade of a Yoshimune sword thrust into the stream. When a Morimasa sword was used instead, every leaf that touched the blade was cut cleanly in two.

Game Notes

In game terms, bladesmiths can craft blades of up to exceptional ability (See the Way of the Unicorn for game rules on item quality). These are not nemuranai, just normal items, though of superior craftsmanship. Legendary items would require legendary circumstances or the aid of a shugenja.

For a fine set of game mechanics on bladesmithing, check out Shinjo Killbeggars rules (URL in the last section).

The Missing Smith

Challenge: A renowned master smith has mysteriously disappeared from his forge-workshop. The daimyo in charge of the district has ordered his samurai retainer (one of the PCs) to investigate before the news spreads and the daimyo be shamed for losing a 'national treasure'.

Focus: The bladesmith was forging late into the night (as was his habit) when his apprentices retired for the day. Next morning, he was gone. His apprentices recall that their master once refused to make a blade for a daimyo from other clan. Is this daimyo responsible?

Strike: The smith has been possessed by the spirit of an ancient bladesmith ancestor who died not having completed his master work. The spirit has brought the possessed smith to its long-abandoned forge in the mountains to finish what it began several centuries ago. The PCs will need the assistance of a shugenja (possibly one of the PCs) to divine the otherworldly nature of the kidnapping. This and some research and exploration should bring them to the hidden forge. The PCs will eventually enter the shrine to find the missing smith sprawled on the floor from exhaustion - without apprentices the heavy work is taking a toll on the old man. The possessing spirit is desperate and will make a bargain with the PCs - help it complete his master blade and he will release the smith. This would be a good opportunity to introduce the basics of bladesmithing to the PCs (possibly picking up some long-forgotten forging secrets?). The PCs will gain great karma and the undying gratitude of the smith and his clan for resolving the problem.

The Broken Sword I

Challenge: The PCs have been summoned to the presence of their daimyo and introduced to a shabbily-dressed stranger who shows them two halves of a broken blade. They are then tasked to aid the stranger to make the blade whole again.

Focus: The stranger is the former daimyo of a disgraced samurai family who lost samurai status when the sword (presented by the 33rd Hantei himself) to a famous ancestor broke in battle. Several master smiths have been hired but none have managed to reforge it. In desperation, the head of the family consulted a learned shugenja who pronounced that only its original maker (or his heirs) can remake it. The PCs have to find a bladesmith of the line of Yoshiye to remake the blade.

Strike: The adventure would involve journeying to remote locales, digging through musty scrolls of family trees to find the smith. The smith could possibly be protected by or lives in an area claimed by Tengu or a tribe of Bakemono. Or the smith may be unwilling until the PCs perform a task for him ("I need the pure waters of lake Norima, on the western edge of the Peerless Mountains", etc.)

The Broken Sword II

Focus: The teenage son of a long-dead samurai approaches the PCs and shows them a fine sword, broken in two. He also tells them a story and requests the PCs' aid, reminding them of the past service done by his father for their respective families.

Challenge: The boy's father committed seppuku in shame 15 years ago, after failing to defend his lord when his famed Morimasa blade broke in battle. His spirit now haunts the broken sword, unable to rest while his shame stains the family's honour. The PCs have to find out what caused the Morimasa (famous for their unbreakability) to break.

Strike A: A curse was placed on the blade because the samurai once killed a hengeyokai (shapechanger) in animal form unknowingly during a hunt. The PCs would have to placate the offended people and possibly offer compensation or service in return for removing the curse.

Strike B: It was an intricate Scorpion plot to discredit the samurai family by cunningly swapping his blade with a very good replica on the eve of a battle. The PCs would have to uncover the plot possibly resulting in confrontation as the guilty party attempts to hide (or kill) the evidence. Presenting evidence of the plot would restore the disgraced family back to favour and possibly gain the PCs a mortal enemy in the culprits.

Epilogue: To round off the adventure, the PCs all dream the same dream the next night - that they are participants in the last great battle which the disgraced samurai took part. This can be played out with the battle rules, just convey to the PCs the smell of blood, the screams of the dying, and the clashing of steel, etc. The wounds should seem real and the PCs should feel that their lives are in danger.

At some point during the battle, the PCs are nearby when a group of enemy Crab horsemen break through the line, charging straight at the daimyo and his personal guard (hatamoto), including the disgraced samurai. The PCs can intervene and help or they can stand by and watch. Regardless of their response, the hatamoto and the enemy engage each other fiercely, with no quarter given.

At some point during the melee, the Crab captain strikes out at the daimyo with a huge tetsubo at which the disgraced samurai lunges, interposing his fragile-seeming Morimasa between his daimyo and the enemy weapon. There is an awesome crack and tetsubo is split (If the PCs have been told this story, they will know that this was when the real sword was broken). Taking advantage of the stunned enemy, the samurai slices off his head cleanly.

If the PCs were spectators, the samurai and the remaining hatamoto finishes off the rest of the enemy. The samurai then turns and bows to the PCs who wake up at this point. If the PCs fought valiantly alongside the disgraced samurai, once the enemy are defeated, he will bow and present the PC who most impressed him with his Morimasa. The PCs wake up at this point. The lucky PC who was given the katana will wake up holding the Morimasa (an exceptional blade 5k3), with a perfect, whole blade once more.

References

The Craft of The Japanese

Sword by Yoshindo Yoshihara, et. al.

The best book available, period. The author, Yoshihara is

regarded as the best living Japanese swordsmith. Also covers

other tasks like scabbard-making which is rarely described in

print.

Tanto: Japanese Knives

and Knife Fighting by Russell Maynard

A concise but complete description of Japanese blades although

its focus is on smaller tanto-sized knives. Excellent diagrams

included.

Shinjo Killbeggar's L5R

Page at www.isu.edu/~crankell/legend.htm

A good set of L5R game rules on bladesmithing.

Don Fogg Custom Knives

at www.dfoggknives.com

A very informative page on forging blades. The author, Fogg is a

noted master bladesmith who specializes in Japanese-style pieces,

crafted as good or better than the Japanese classics, but at an

affordable price. A good place to start for those who want to own

a real katana in the US.

*** End ***